| Fashion Waifs Disappearing

The Fashion eZine - Anorexia

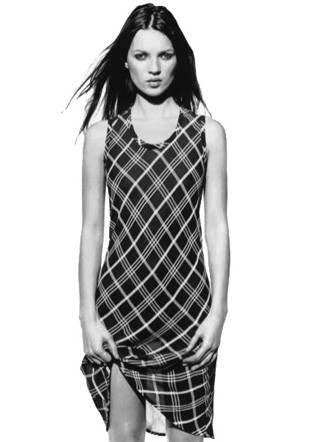

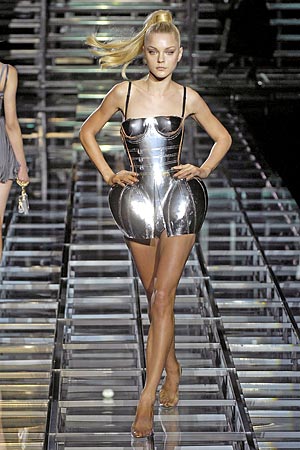

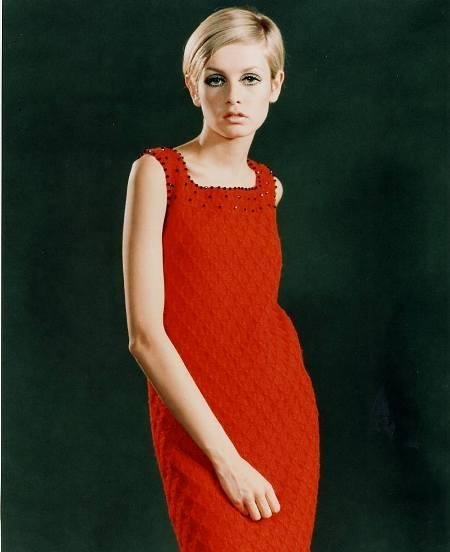

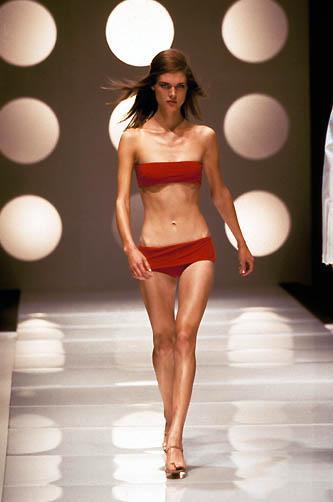

Curves are SexyPrada's new rounded look is in and the fashion world is rediscovering that curves are sexy. The standard catwalk waif is losing power. Miuccia Prada, the most-watched trendsetter in the fashion world, has signalled a move to curvier models by choosing a busty Lara Stone to parade a new sweater on the Milan runway where before Prada had stuck almost exclusively to stick-thin girls commonly known as waifs (a dime a dozen anorexic models). Paris will follow Prada's lead as designers responding to health concerns sparked by the deaths of three South American "size zero" models and their influence on young girls. Lara Stone, a size 8 Dutch model with a 86cm bust, was cast to model a fine-knit but virtually see-through top to show off her breasts. "The casting was personal to her," said the designer's spokeswoman in Milan. The performance by a bra-less Stone, age 23, contrasted with the far thinner and flatter-chested models who followed behind her. Paula Reed, style director of Grazia magazine, who also sat on an inquiry into models' health for the British Fashion Council, was one of those present. "It is good to see Prada using healthy-looking models," she said. "Miuccia Prada is such an influential designer that others are bound to copy her. She is a mother, too, so this is an important message she is sending to the fashion industry." But how did this finally come about?

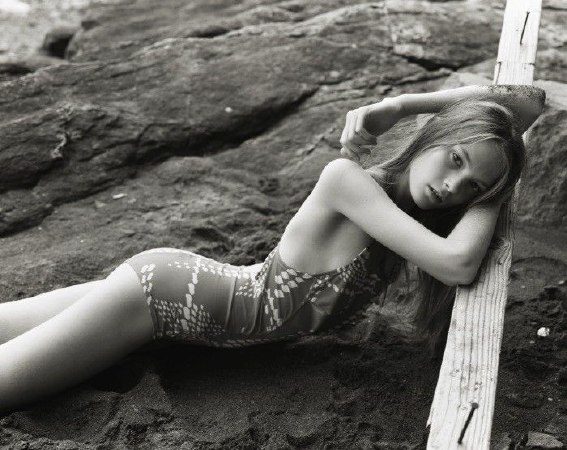

How Fashion Magazines Killed The Unloved WaifThe fashion industry is surprisingly haphazard. That's why so few fashion houses can successfully go public and so many go bankrupt. Fashion, with its meandering course and dependence on fickle customers with fluctuating bank accounts, doesn't tolerate the sort of business plans that make other industries more predictable and bankable. But a year ago, a frail, washed-out creature called the waif almost did fashion in. And in what may give conspiracy theorists a sense of satisfaction, magazine editors, certain designers and retailers joined forces like characters in an Agatha Christie novel to deal a death blow to the waif, whom most magazine readers and store customers had rejected. This is the story of the conspiracy to haul fashion away from a look that wasn't selling clothes or makeup. In its place is glamour and a healthy dose of voluptuous breasts, which has been interpreted as everything from 1940's Marlene Dietrich to 1970's Bianca Jagger. The September issues of fashion magazines, the business's manifestos for fall, are normally peppy, inspirational roundups of designer notions intended to send readers straight to the mall for a wardrobe update. Not this time. September's issues are a back-of-the-limousine ride to Studio 54, with Helmut Newton, the photographer of that era's most sexually charged photographs, as chauffeur. Even Mirabella, which usually offers shelter in a storm of fashion change, showed off leopard prints, fishnet hose, stilettos, fake fur and sequins.

The effect has less to do with designers' runway visions than the way the look is styled. And the looks that are authentically 1970's seem to be mostly unavailable in stores. Any woman waving her page from, for instance, Allure magazine's "Dressed to Kill" layout would have a hard time tracking down the Junko Shimada snakeskin jacket that opened the spread (available at Junko Shimada in Paris), or the Kitty Boots patent leather skirt (there was only a phone number listed). "The 70's revival, the whole Helmut Newton thing, is across five different magazines this month," observed Richard Martin, the curator of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. "I can't think of another fashion-magazine moment not seeking differentiation but agreeing on this, which is a New York stylist's take on the world. Why would there be so much consensus about something reaching beyond the fashion per se?" The answer lies mostly in the fact that when magazine editors began asking for glamour, particularly the 1970's variety, the collections for fall were already designed. Now, stores and designers are playing catchup with their publicity machines, the magazines. The glamour campaign began during the March fashion shows, when Anna Wintour, editor in chief of Vogue magazine, met with the fashion directors of department stores to spread the word. Vogue, she said, believed in one thing: glamour.

"She first brought it up," said Joan Kaner, the senior vice president and fashion director of Neiman Marcus. "This was the first time we'd ever gotten direct input, and at the time I hadn't seen much of the glamour thing." Later, Ms. Kaner saw the collection of John Galliano, a designer Vogue helped get back on the runway, from finding backing to securing accessories. Not surprisingly, he offered exactly what Vogue wanted. "When I saw John Galliano, that was the beginning of it all," Ms. Kaner said. "Having been in this business a long time, you can be told something and you have to respond to it." Neiman Marcus did respond. Its fall catalogue, timed to the release of fall magazines, has elegant script declaring: "Glamour circa 1994." The next manifestation, the 1970's version of glamour, was epitomized by Marc Jacobs's fall collection, which almost all big fashion magazines photographed lavishly. "Vogue certainly has gone 100 percent with this look," Mr. Jacobs said. "They reflect that glamour not because I did it, but because they reflect it right now in terms of fashion." Vogue was also instrumental in helping Mr. Jacobs restart his collection, with the magazine's accessories editor, Candy Pratts Price, promoting his and Mr. Galliano's use of diamonds in their shows. Diamonds were a key part of Vogue's battle cry.

"We spoke to Anna, we spoke to Women's Wear Daily and we spoke to Harper's Bazaar," Kal Ruttenstein, Bloomingdale's fashion director, said of the glamour movement. "They all said it to us. It was a collaboration of stores and magazines, and customers being tired of too-plain clothes and wanting to return to shape. It also gave something new." But Mr. Ruttenstein stressed that the magazines are pushing the glamour look for day, and "it's an advanced customer who will wear sequins for day." Which could make the new glamour as irrelevent to real women as the old waif was. "We're a department store, and we have to feature looks for women in many different points of view," he said. "Not everybody wants to be or should be glamorous." For Vogue, the demands of advertisers, readers and some key designers had peaked in March. American accessory designers, led by the jewelry designer Robert Lee Morris, staged a small uprising before the European fashion shows, taking the magazine to task for ignoring handbags, shoes, scarfs and jewelry in favor of stark, minimalist layouts.

|

|

Waifs don't sell Glamour"From a purely business standpoint, the waif thing affected us across the board," said Ronald A. Galotti, the publisher of Vogue. "Retailers weren't moving product, designers were trying to identify themselves with grunge, the waif look and absence of color and shape, and there's not a lot you can sell people. If you can't sell it, you can't advertise it. Thank goodness Anna had her finger on the pulse. She wanted to lead this charge back into glamour and work with designers." By May, Vogue was able to publish its new charter on its editorial page. The headline was "Strong and Sexy." It declared Nadja Auermann, the towering German blonde who was on the September covers of both Harper's Bazaar and Vogue, the model of the moment with her "steely femininity." And as fashion magazines are wont to do, the piece described the glamour movement it was creating as if it were already happening on the streets. It read: "From Paris's trendy Les Halles neighborhood to New York's Madison Avenue, women are trading in grunge and minimalism for a decidedly polished and tailored look that combines the timeless, sleek cut of a masculine pantsuit circa 1975 with the hard-edged, flash-in-your-face stance of a Helmut Newton photograph and the gusto (but not the shoulder pads) of the 80's working woman."

"It wasn't working," Ms. Wintour said of the waif. "The granny slip dress with sneakers is too difficult. And no makeup and dirty hair is not what the Leonard Lauders of the world want to see." Mr. Lauder is the president of Estee Lauder, a big advertiser in fashion magazines. While she was emphatic that the death of the waif was imperative, Ms. Wintour conceded that the process was going a little fast for the average woman. "A little slowing down might be a not bad thing for fashion, giving her time to adapt and change," Ms. Wintour said. "We need a period of time for clothes to get in stores." Elizabeth Tilberis, the editor of Harper's Bazaar, also predicted that the busty and athletic glamour girl would outlast her frail predecessor. Harper's Bazaar weighed in in July with its version of hard-core glamour called "Shock Treatment." Ms. Tilberis said, "Once this one gets going, a lot more people will be thanking us for this look than the waif."

Mr. Galotti, Vogue's publisher, said that for the first time, Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor and Nordstrom had mapped out their advertising a year in advance, after a year of last-minute ad purchasing that he put down to fear of the waif. While it appears that financially the dictate couldn't have come at a better time, designers are scrambling to keep up. Calvin Klein, who is in the odd position of having been the most generous employer of the waif and one of the icons of the Studio 54 era, made an immediate shift in his advertising, and the waif was gone. "Even Calvin is talking red lips," Ms. Wintour said. "Every ad you see is glamour, glamour, glamour: fish net, high heels, red lipstick. You can't make change happen without extremes. That's the extreme." Richard Tyler, the designer for Anne Klein, produced cyber-70's advertising layouts shot by Steven Meisel. While his runway show had none of the fright-wig feeling of the ad campaign, Mr. Tyler said decade of the 70's was in his mind when he designed the collection. "A lot of the clothing had a very 70's feel," he said. "But with an advertising campaign you have to take it another step." Others, like Isaac Mizrahi, have profited editorially from the glamour trend by coincidence. "It's really not reflected in retail," Mr. Mizrahi said of the look that has been featured so prominently. "Maybe it will be next month. For me, it's not about 1970's glamour. It's more about 1990's magazines." Believers in real clothes for real women have watched the stilettos come out with a rueful patience. This, too, they know, shall pass. "It's kind of weird, because I think sometimes the messages put out there are too abrasive," said Donna Karan, the designer. "Grunge, they said, was the death of fashion. Then monastic was the death of fashion. Now this. Fashion links on to something so hard and then generalizes it and exaggerates it and frightens the customer."

So is ultra-thin going out of fashion?You can never be too rich or too thin, or so the saying goes. But moves at major catwalk shows to stem the use of underweight models suggest the tide may be turning. The debate kicked off when Madrid fashion week decided, in response to local government pressure, to ban models with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 18. Health experts recommend a BMI - a calculation based on height and weight - of between 18.5 and about 25. Milan fashion week then opened with a plus-size show - and the announcement of a new code of conduct from February, under which models will have to carry a health certificate. Action may have been prompted by the death of a 22-year-old Uruguayan model who collapsed after a catwalk show in August. She had reportedly eaten little but leafy vegetables for months in order to lose weight. Commentators have also questioned the negative impact of underweight models on ordinary girls' and women's body image, amid concerns over anorexia. Of course, whether the move away from the super-skinny gathers weight will not be down to the models - it's the modelling agencies, designers and fashion magazines who hold the clout. The question is, will the powerhouses of the industry listen to the chorus of concern - or argue they are simply meeting the desire of the buying public to see clothes on waif-like women?

Designer's aestheticThe French Couture Federation told reporters it had decided not to speak on the topic in the run-up to Paris Fashion Week, which starts on Sunday. Federation President Didier Grumbach had previously been quoted in the media as saying "everyone would laugh" if the measures taken in Madrid were seen in Paris. The British Fashion Council, which runs London Fashion Week and has close links to the UK's top design colleges, says it is willing to participate in the debate - but is not taking a lead. "It's not our role to interfere in the aesthetic of any designer but we are open to a broader discussion about these issues," a spokeswoman said. Italian designer Giorgio Armani, writing in the UK's Independent newspaper before London Fashion Week, admitted he preferred models "on the slender side" because "the clothes I design and the sort of fabrics I use need to hang correctly on the body".

Bustier/Athletic WomenHowever, there is some evidence of a shift away from the current trend for American size 0 (British size 4) women, among them one of the UK's most successful models, 18-year-old Lily Cole. British designer Sir Paul Smith, speaking during London Fashion Week, said he believed the measures taken in Madrid might persuade casting agencies to consider slightly larger women for the catwalk, and the Clothes Show Live, a high-profile UK fashion event, has said that from December no models smaller than a British size 6 will be used. But observers warn it may take a long time for attitudes to change. Lerato Moloi, a successful South African model and former Face of Africa finalist who was told to lose weight when she went to New York, told reporters that the problem was the culture that had developed in the US and Europe. "It's a problem that has been going on for decades but the designers still use [underweight girls] because they can - and they will as long as they have a clientele that prefer it," she said. "At the end of the day, it's the designers' prerogative."

She cites South Africa, where models are a "peachier" more rounded size, as an example of a country whose growing fashion industry is not dictated to by the West. "We've embraced a completely African sense of everything. The African woman's body is fuller naturally and, even though we have a mixture of cultures in South Africa, we tend to prefer a woman who looks normal or healthy."

Unrealistic ModelsDr Emma Halliwell, a psychologist at the University of the West of England, says she hopes the moves in Madrid and Milan mean the fashion industry will start to take more responsibility for models' health. She points to studies showing that over the past 30 years models in magazines have grown steadily thinner, so that now they tend to be about 15% under a healthy weight. Anorexic models could certainly gain an extra 15 pounds of muscle, breast fat and hips. "There's a growing disparity between the bodies women have and the ideal being displayed to them," she said. Meanwhile, research conducted jointly with Dr Helga Dittmar, of Sussex University, suggests models do not have to be ultra-thin to sell products effectively - an argument often used by advertisers. Nonetheless, Dr Halliwell foresees a lot of resistance in the fashion industry to a move towards healthier-looking models. Ms Moloi agrees: "I'm hoping it's not just a trend and they will stick with it - but it will be a while before it changes lock, stock and barrel."

| |