| Cuteocracy

The Fashion eZine - Cuteness & Style

The Apotheosis of Cute

How fluffy bunnies, bouncy kittens, and the Clinton era brought cuteness to an awful climax.By Annalee Newitz SOMETHING CUTE IS happening to America. On television the squeaky Pokémon and Digimon are living in a universe whose main physical characteristics are orange squishies and pink smooshies. Harry Potter, the embodiment of nice-little-boy-ness, is exuding a vaguely pedophiliac charm on movie screens. Teenage girls are mobbing the Sanrio store for the latest Hello Kitty hair bands and dropping into the Paul Frank boutique for teeny T-shirts covered with hair-curlingly sweet cartoons of a spotted bunny-kitty-mousie-puppy creature who likes to eat birthday cake. Lipsticks are pink and sparkly; blouses are festooned with lace; fluffy stuffed animals serve as fashion accents. San Francisco's feminist sex-toy store Good Vibrations even has a glittery strap-on dildo harness that its ads describe as "so CUTE!" Meanwhile, Britney Spears and Lil' Kim remind us that the "suck that lollypop like you mean it" Lolita look never dies. We are living in what a friend of mine calls "the cuteocracy," where the cutest person, place, or thing wins. Realism is out – unless it's the hyperconstructed reality of Survivor – and the supernaturally ugly aesthetic of the X-Files has gone the way of presidential candidate Ross Perot. Perhaps it's unsurprising that, as the United States takes a dark political turn with its unceasing war on terrorism, people are hungry for sweetness and light.

On San Francisco's Haight Street, where retail outlets bulge with cute items of every description, shoppers are looking for what Durey Kim, store manager at X Generation, calls "cute, old-fashioned clothes that are girly and pretty, like what people wore in the early 1980s." Jeffrey Caballero, manager of the Paul Frank store, says that his customers "grew up with Disney and other iconic figures, so there's something calming and fun about putting that kind of cuteness into everyday fashion." Cuteness may be calming and fun, but it's also an ideal mask for something more unsettling. The national craze for cuteness has turned the innocent optimism of Hello Kitty into a hollow, cynical commercialism. Many of the images and icons we call "cute" came from idealistic, hopeful social movements of the 1960s and the exuberant subcultures of early-1990s clubbers and digital dreamers. But today cuteness is starting to feel like fake, mall-bought conformity. As the war on terrorism quickly reduces our complicated national situation to a simplistic cartoon, it seems that reactionary politics can be cute too. The fuzzy-bunny regime is telling you to forget; be a kid; don't worry. And cuteness, as lovable a style as it may be, is turning ugly. Mommy, where does cute come from? The appeal of cuteness is as old as the giggle, but today's cuteness craze has its roots in the decidedly uncute early days of the Clinton administration, a time when the national mood was tilting toward the progressive and many citizens were still trying to figure out exactly what had happened during President George Bush Sr.'s video game-style Gulf War. The cold war was officially over, and the war on terrorism was just a twinkle in President George Bush Jr.'s eye. Fashion, music, and film were focused on grunge and hip-hop, two styles that were urban, gritty, and downscale. Self-styled white trash kids from the Pacific Northwest, obsessed with the antifashion of thrift-store jeans and no-brand T-shirts, were giving voice to a generation captivated by music about passionate self-hatred. Meanwhile, inner-city kids were inspiring what fashion mags called "street chic" and using their music to rage about political injustice and the short, brutish ghetto life that had been created, in large part, by the Reagan-Bush administrations' social policies.

But chubby, baby-faced Clinton promised the disaffected something better. He swept into office on the bouncy, happy music of Fleetwood Mac, whose "Don't Stop" (thinking about tomorrow) was the official inaugural song of the administration. The first lady was talking about a universal health care plan. And underground raves were spreading the word about PLUR – peace, love, unity, and respect. Probably the first hints that America was about to embark on a veritable odyssey of cute came from the ravers and club kids of that era, whose fashions and music were themselves inspired by a combination of 1960s hippie bliss and 1970s disco frenzy. Raver-friendly happy faces, day-glo accessories, psychedelic patterns, and extremely weird, plushy sneakers began to find their way into urban boutiques, and later into suburban malls. Like true cutie-pie mavens, club kids embraced the enigmatic but peaceful messages of Sanrio and Paul Frank, whose simple, beatific cartoon characters appealed to the childlike mind-set of people on ecstasy. The trippy cuteness of rave culture had its counterpoint in the burgeoning Web industry of the mid 1990s. Digital designers had to deal with a medium whose flexibility was, at least in the early days, fairly minimal. Basic, bright, cartoony images filled the Web as it evolved into a phenomenally successful mass medium. Wired magazine took its cues from early digital design, playing with neon colors and exaggeratedly low-res graphics; later, Web zines like Suck and Word were famous for their random cartoony images, which set the tone for dozens of other Web culture sites. You might say that cuteness was the aesthetic of early Web sites, and digital cuteness influenced graphic design generally. Cuteness as we know it also owes much to Asian pop culture – especially from Japan. Although Godzilla, Hello Kitty, and Robotech had been staples in America for decades, the 1990s saw an unprecedented escalation in the availability of Japanese anime (cartoons), manga (comic books), fashions, movies, and ideas in the United States. According to Renee Solberg, marketing associate at Viz, one of the largest distributors of anime and manga in the United States, manga sales have gone up by 200 percent just in the last year – and a similar trend could be seen throughout the latter half of the 1990s.

American kids began to imitate the Japanese styles they saw in popular Japanese fashion magazines like Fruits, which featured Tokyo teens in baby-doll dresses, giant shoes, "Raggedy Ann" getups, and Disney T-shirts. American zines about Asian pop, such as Giant Robot and Asian Trash Cinema, flourished. Japanese icons Hello Kitty and Pokémon appeared on every sort of consumer item, from vibrators to bulky plastic watches. Meanwhile, bubblegum babes and superheroic boys from Hong Kong action movies became a hot Hollywood import. By the end of the 1990s nothing was cooler than Asian pop. And nothing was cuter. The extra-cuddly Clinton legacy Americans were falling in love with Asian culture at the same time that their corporate masters and politicians were falling out of love with it. The early 1990s were an era when people talked about "the trade war with Japan," a time when the news was packed with stories about how the United States had entered a new "economic war" with various Asian countries. Books like Michael Crichton's Rising Sun (1993) and George Friedman and Meredith Lebard's The Coming War with Japan (1991) trumpeted theories about how the Japanese were planning to take over America with their superior capitalist ways. Some of the fascination with Asia in the United States clearly had more than an edge of fear and loathing to it. Clinton's warm-fuzzy image was also masking a political agenda that was less than friendly. Cuts in social spending during his administration finished the dirty work that the Reagan-Bush era had begun. The division between rich and poor became a gaping wound; according to Left Business Observer editor Doug Henwood, "[In 1998] poor households – those in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution – still hadn't recovered 1989's level. And this in a time when GDP was up almost 30 percent after adjustment for inflation – 14 percent per capita, after accounting for population increase." In many regions tax cuts also made a mockery of public education and welfare. The Asian stock-market bubble, which grew so huge partly as a result of Japanese investment, burst in 1997 and '98, trashing the economies of Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia. More recently, the United States Internet bubble burst too. Places and things we had once associated with fun were now connected with failure and destitution. Even the rave scene, once filled with exuberance and hope, began to fragment and deteriorate. Huge, mainstream dance parties packed with thousands of clubbers replaced the smaller, more friendly raves. Bigwig promoters raked in the cash, and indie flicks like Go portrayed club kids as aimless and strung out, people whose passion for PLUR had become nothing more than a quest for good drugs. As the Clinton era drew to a close, it was obvious that the president, elected as a reformer, had hardly changed the course of the nation at all, except superficially. One might say that Clinton slapped a happy-face sticker on top of our social problems, rather than fixing them. The only thing cute about his regime was the squeezably soft, apple-cheeked Monica Lewinsky, who now makes her own line of fuzzy, boppy designer handbags and looks like Hello Kitty – with her little purse – come to life. All the cultural trends that seemed overwhelmingly cute during the Clinton era – raves, digital design, peppy products of the Asian economy, even reform politics – had become far less appealing by the time Bush took office in a crescendo of national ambivalence. And yet, weirdly enough, cuteness raged on. The politics of cute These days cuteness has lost any subversive edge it might have had back in the days when raves and manga in the United States were still mostly the purview of underground culture enthusiasts. Cute is a consumer item, a mainstream aesthetic. When I plunged into the cutesy side of retail culture on Haight Street, I eventually found voices of dissent, people who had become suspicious of what those tiny pink dresses and itsy-bitsy sparkly barrettes might mean. Ironically, it was at one of the trendiest cutie-pie clubber boutiques that I first heard a critique of cuteness. Kristin Lysko, who works at the boutique in question, says emphatically, "Cute is something that I don't want to be." She and her colleague Katrina associate cuteness with "pink and dainty clothes," "fakeness," and "girliness," and they seem genuinely disturbed by the fact that customers who seek out the cute look are overwhelmingly teenage girls. Katrina is concerned about what this says about the state of gender relations as a whole. "Guys wanting only little cute girls is a problem as a social thing generally," she says. |

|

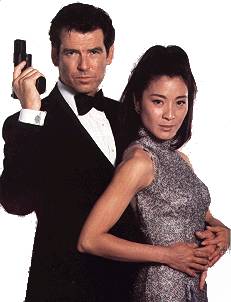

Just a cursory look at female celebrities of the last several years – from Britney Spears and the girls of Dawson's Creek to fashion-art babe Björk – substantiates Kristin and Katrina's fears. One might say that the cuteness fad is a new version of heroin chic – an impossible, unhealthy standard of beauty that idealizes delicate, vulnerable, or childlike female bodies. Stores like X Generation and Urban Outfitters, which cater to the cute crowd, rarely carry women's sizes that go above an eight, and the majority of their clothing is designed for the size-three set. Adding insult to the already injured egos of girls whose bodies aren't as perky as the allegedly "real" ones on MTV's Road Rules, cuteness also glamorizes babyish, mindless behavior in women. After all, as we learn in Marie Moss's new book about Hello Kitty, called Hello Kitty Hello Everything! (Abrams), this cute icon is in the third grade. And that's about the age bracket in which a cute girl is supposed to exist, perpetually cooing over dollies, stickers, and boys, never growing up and becoming a competent, independent adult. Perhaps the ultimate form of feminine cuteness can be found in the miniature, singing twin girls from Japanese monster movie Mothra. Dressed in flowers and bikinis, these magic twins are about a foot tall, speak mostly in squeaks, giggles, and songs, and live inside a very pretty box. Their only use is rather secretarial: the twins communicate with Mothra when men ask them to do it, performing this simple service with bashful smiles and grateful chirps of "Thank you, thank you!" The Asian-philia at the heart of America's obsession with cuteness is hardly motivated by the same innocence that animates the little girls in Hayao Miyazaki's orgiastically cute film My Neighbor Totoro. Possibly Asian pop culture seems so appealing in the United States because it's "safe," a nonconfrontational and friendly product from a region whose power threatens U.S. dominance. There's something mildly creepy about the way cuteness – at least as it's consumed in America – reduces all of Asian culture to its most precious, infantile, and fluffy form. Yum Pop is one of the more cutting-edge cute chic designers in the United States, producing the popular teenybopper-goth Emily line of products as well as several collections of Asian-inspired T-shirts, bags, and accessories. One Yum Pop T-shirt features a smiling bowl of noodles and boasts the slogan, "Miso happy!" Yum Pop's popular airline bag has a little panda zooming through the air in a plane, above the legend "Smile hi club." Both items are heartbreakingly adorable, and yet part of their appeal depends on arch references to stereotypical Asian accents and poorly executed attempts to use English idioms. University of Virginia professor Eric Lott once described American blackface as "love and theft": whites acted out their conflicted relationship with blacks by paying homage to African American culture and stealing it at the same time. There's a certain amount of love and theft involved in the Asian-pop side of American cuteness, too. Of course, there's nothing inherently wrong with "stealing" Asian icons for deployment on American T-shirts. It's more a question of what gets done with these icons once they've been claimed.

As far as mainstream American culture is concerned, Asian pop is only cool insofar as it's associated with the characteristics of cuteness: frivolity, simplicity, and harmless little children. Sanrio, while undeniably appealing, is hardly going to teach Americans to respect the Japanese as their honorable equals, if you know what I mean. There's also a difference between Japanese kids consuming Sanrio in Japan and Americans fetishizing Sanrio in the United States. In Asian countries, cute pop baubles are only a small part of the mainstream culture. But in America, regardless of whether the American consumers in question are African American, Asian American, Euro-American, or whatever, they are liable to consume Asian pop cuteness outside of its Asian context. In other words, for the Asian pop-obsessed American, all of Asian culture might get boiled down to its cutest incarnation. Yet when somebody who lives in Asia buys a Hello Kitty purse, she or he is unlikely to be convinced that the entirety of Asian culture is represented by weensy animals and childish cartoons. Kristin, one of the few critics of cute I found on Haight Street, says it makes perfect sense to her that cuteness has continued to be popular during a time of national fragmentation and war. "Cuteness is about fakeness and avoiding reality. You can just put yourself into cute mode and everything's fine," she suggests sarcastically. And indeed, the serious business of cuteness does seem to be all about what the late culture critic Michael Rogin called "cultural amnesia," in which an entire society forgets about its problems by consuming mass media. Afraid of terrorists? Forget about complicated global problems and go see Monsters, Inc. Lose yourself in a simple story about big, fuzzy, nice monsters and a girl who speaks only in darling little blurts of gibberish. And hey, if poverty in America is bothering you, just tune in to reruns of The Simpsons, who prove that it's supercute and always entertaining to be lower class. Cultural amnesia, according to Rogin, is all about using appealing images to wipe out our memories of painful historical and political realities. Looked at from this perspective, cuteness is a kind of cultural decoy, a soothing and simple distraction from a world whose boundaries and problems are becoming more mind-bogglingly complex by the day. It's no coincidence that the recent run on U.S. flag fashions dovetails nicely with cuteness. You can get weensy teddy bears waving American flags and neato sparkly tops and bell-bottoms in red, white, and blue. There's no contradiction, in other words, in the partnering of retrograde nationalist spectacle and mainstream raver chic. Ultimately, the danger of cuteness is that it's a style that plays into the most conservative American tendencies. It vaunts a frivolous, impotent femininity, cartoonish racial representations, and a passive, apolitical view of the world. Collecting stuffed animals, baby-doll dresses, and cartoon-adorned handbags is also a way of regressing into a childlike state. The cute regime regresses all of us to credulous children, so that when Papa Bush tells us we need to bomb those bad people in Afghanistan and Somalia, we know he's right. After all, he's our nice friendly friend. He even does sweet things like thank his mommy for teaching him to chew carefully when he eats pretzels. It's a slippery slope from cuteness to sheer mindlessness.

Cute and anti-cute:Of course, not everybody is buying into cuteness. There are already indications that the cute craze has reached its frenzied peak and is about to get dumped into the ash can of history. Chad Lott, a dead ringer for Partridge Family-era David Cassidy who works at Sparky's in the Haight, is sick of cute. "I'd like to see less cute and more of the slutty-rocker-girl look," he says. Designers may be churning out frothy dresses, but there's also a punk nostalgia movement going on, and back in the early 1970s, punk was a direct protest against the mindless cuteocracy of the hippie counterculture. Meanwhile, Pokémon fatigue has swept the nation, and one of the season's most-anticipated, potentially cute films, The Fellowship of the Ring, was hardly that: its dark portraits of political fragmentation and power run amok were far more compelling than the occasional moments of hobbit hugginess. Perhaps more interestingly, the artists and subcultures who deal in cuteness are generating their own ironic self-criticism. My coworker Sarah Han's cute, crocheted yarn creations, including her "Poolets," a line of fluffy poop dolls, recently caught the attention of buyers for the Giant Robot store. Soon, you'll be able to buy the cigar-shaped "torpedo" poop or the more traditional soft, bumpy little pile. Han is even planning a crocheted diarrhea puddle and some constipation pebbles. There's something distinctly subversive about marketing shit as cute, and these puffy brown creations definitely call attention to the real meaning behind so many cute fashions and styles. More mainstream examples of the cute critique can be found in the Powerpuff Girls TV show, which manages to be both overwhelmingly pink and remarkably sharp-edged. The girls are cute and little but also smart and tough. And the show is full of dirty jokes and political references that poke holes in the bubbleguminess of most kiddie cartoons. One might extend these comments to cover subterranean Web sites like the cartoony Plastic.com and Slashdot.org, which look kinda cute on the outside but offer prickly social criticism and snarky anticorporate commentary.

Even the Harry Potter phenomenon offers a ray of hope for fans who want to rescue the cute aesthetic for a politically progressive purpose. Although the Harry Potter movies are nothing more than adorable distraction, the books are something else altogether. In between saccharine passages about dragons, exploding candies, and the finer points of Quiddich, author J.K. Rowling reveals the class divisions that haunt every pupil at Harry's exclusive school, Hogwarts. The poor kids are picked on by the rich kids, and the rich adults are able to decide the fates of the poor ones. Rowling makes it clear that money is still a political issue, even in the wonderful world of magic. Cuteness in itself is just a style. But over time, the squishy, fluffy, woopieness of cute has developed a rich cultural meaning. There's more to pink and baby blue T-shirts than sheer yumminess. Although it might be cute when Hello Kitty's precious little face is all over your house, it's less than sweet when the cartoony simplicity of so much contemporary American culture seeps into our political rhetoric. I love the Sanrio store as much as the next Asian pop-obsessed chick, and I'll freely admit that I often wear a smooshie hat with a big smiley-faced ladybug on the front of it. We don't have to throw away all our Godzilla DVDs to be critical of the cute regime. Ultimately, the problem is not "cute," but how and when we use it.

| |